Pitfalls and potential

Introduction

This page shows how you can implement the examples provided in Chapter 2 of O’Sullivan and Unwin (2010). To get most out of this, go through the examples slowly, line by line. You should inspect the objects created and read the help files associated with the functions used.

The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem

Below we recreate the data shown on page 37. There is one region that is divided into 6 x 6 = 36 grid cells. For each cell we have values for two variables. These gridded data can be represented as a matrix, but the easiest way to enter the values is to use a vector (which we can transform to a matrix later). I used line breaks for ease of comparison with the book such that it looks like a matrix anyway.

# independent variable

ind <- c(87, 95, 72, 37, 44, 24,

40, 55, 55, 38, 88, 34,

41, 30, 26, 35, 38, 24,

14, 56, 37, 34, 8, 18,

49, 44, 51, 67, 17, 37,

55, 25, 33, 32, 59, 54)

# dependent variable

dep <- c(72, 75, 85, 29, 58, 30,

50, 60, 49, 46, 84, 23,

21, 46, 22, 42, 45, 14,

19, 36, 48, 23, 8, 29,

38, 47, 52, 52, 22, 48,

58, 40, 46, 38, 35, 55)

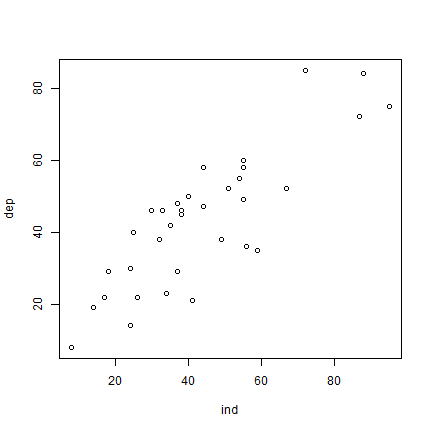

Now that we have the values, we can make a scatter plot.

plot(ind, dep)

And here is how you can fit a linear regression model using the glm

function. dep ~ ind means ‘dep’ is a function of ‘ind’.

m <- glm(dep ~ ind)

Now let’s look at our model m.

m

##

## Call: glm(formula = dep ~ ind)

##

## Coefficients:

## (Intercept) ind

## 10.3750 0.7543

##

## Degrees of Freedom: 35 Total (i.e. Null); 34 Residual

## Null Deviance: 12080

## Residual Deviance: 3742 AIC: 275.3

To get a bit more information about m, we can use the summary

function.

s <- summary(m)

s

##

## Call:

## glm(formula = dep ~ ind)

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 10.37497 4.12773 2.513 0.0169 *

## ind 0.75435 0.08668 8.703 3.61e-10 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for gaussian family taken to be 110.0631)

##

## Null deviance: 12078.8 on 35 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 3742.1 on 34 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 275.34

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 2

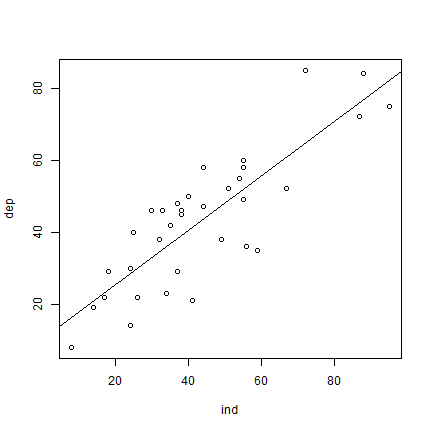

We can use m to add a regression line to our scatter plot.

plot(ind, dep)

abline(m)

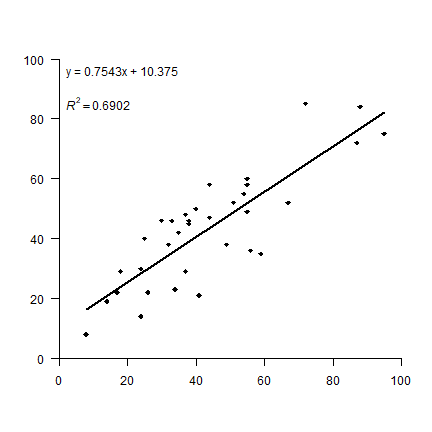

OK. But let’s see how to make a plot that looks more like the one in the

book. I first set up a plot without axes, and then add the two axes I

want (in stead of the standard box). las=1 rotates the labels to a

horizontal position. The arguments yaxs="i", and xaxs="i" force

the axes to be drawn at the edges of the plot window (overwriting the

default to enlarge the ranges by 6%). To get the filled diamond symbol,

I use pch=18. See plot(1:25, pch=1:25) for more numbered

symbols.

Then I add the formula by extracting the coefficients from the

regression summary object s that was created above, and by

concatenating the text elements with the paste0 function. Creating

the superscript in R2 also takes some fiddling. Don’t worry

about understanding the details of that. There are a few alternative

ways to do this, all of them can be found

on-line,

so there is no need to remember how to do it.

The regression line should only cover the range (min to max value) of

variable ind. An easy way to do that is to use the regression model

to predict values for these extremes and draw a line between these.

plot(ind, dep, pch=18, xlim=c(0,100), ylim=c(0,100),

axes=FALSE, xlab='', ylab='', yaxs="i", xaxs="i")

axis(1, at=(0:5)*20)

axis(2, at=(0:5)*20, las=1)

# create regression formula

f <- paste0('y = ', round(s$coefficients[2], 4), 'x + ', round(s$coefficients[1], 4))

# add the text in variable f to the plot

text(0, 96, f, pos=4)

# compute r-squared

R2 <- cor(dep, predict(m))^2

# set up the expression (a bit complex, this)

r2 <- bquote(italic(R)^2 == .(round(R2, 4)))

# and add it to the plot

text(0, 85, r2, pos=4)

# compute regression line

# create a data.frame with the range (minimum and maximum) of values of ind

px <- data.frame(ind = range(ind))

# use the regression model to get predicted value for dep at these two extremes

py <- predict(m, px)

# combine the min and max values and the predicted values

ln <- cbind(px, py)

# add to the plot as a line

lines(ln, lwd=2)

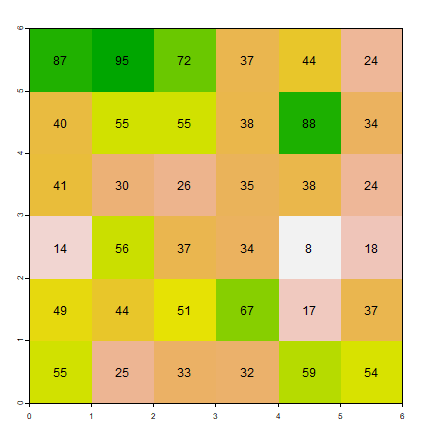

Now the aggregation. I first turn the vectors into matrices, which is

very easy to do. You should play with the matrix function a bit to see

how it works. It is particularly important that you understand the

argument byrow=TRUE. By default R fills matrices column-wise.

mi <- matrix(ind, ncol=6, nrow=6, byrow=TRUE)

md <- matrix(dep, ncol=6, nrow=6, byrow=TRUE)

Question 1: Create these matrices from ind and dep

without using byrow=TRUE. Hint: use the t function after

you made the matrix.

The type of aggregation as shown in Figure 2.1 is not a very typical

operation in the context of matrix manipulation. However, it is very

common to do this with raster data. So let’s first transform the

matrices to objects that represent raster data, SpatRaster objects

in this case. This class is defined in the terra package, so we need

to load that first. If library(terra) gives this error:

Error in library("terra") : there is no package called ‘terra’ you

need to install the package first, using this command:

install.packages("terra").

# load package

library(terra)

## terra 1.8.23

# turn matrices into SpatRaster objects

ri <- rast(mi)

rd <- rast(md)

Inspect one of these new objects

ri

## class : SpatRaster

## dimensions : 6, 6, 1 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

## resolution : 1, 1 (x, y)

## extent : 0, 6, 0, 6 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

## coord. ref. :

## source(s) : memory

## name : lyr.1

## min value : 8

## max value : 95

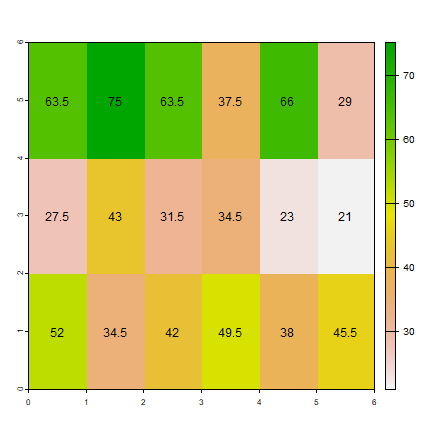

plot(ri, legend=FALSE)

text(ri)

The “terra” package has an aggregate function that we will use. We specify that we want to aggregate sets of 2 columns, but not aggregate rows. The values for the new cells should be computed from the original cells using the mean function.

Question 2: Instead of the ``mean`` function What other functions could, in principle, reasonably be used in an aggregation of raster cells?

ai1 <- aggregate(ri, c(2, 1), fun=mean)

ad1 <- aggregate(rd, c(2, 1), fun=mean)

Inspect the results

as.matrix(ai1)

## lyr.1

## [1,] 63.5

## [2,] 75.0

## [3,] 63.5

## [4,] 37.5

## [5,] 66.0

## [6,] 29.0

## [7,] 27.5

## [8,] 43.0

## [9,] 31.5

## [10,] 34.5

## [11,] 23.0

## [12,] 21.0

## [13,] 52.0

## [14,] 34.5

## [15,] 42.0

## [16,] 49.5

## [17,] 38.0

## [18,] 45.5

plot(ai1)

text(ai1, digits=1)

To be able to do the regression as we did above, I first combine the two

SpatRaster objects into a (multi-layer) object.

s1 <- c(ai1, ad1)

names(s1) <- c("ind", "dep")

s1

## class : SpatRaster

## dimensions : 3, 6, 2 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

## resolution : 1, 2 (x, y)

## extent : 0, 6, 0, 6 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

## coord. ref. :

## source(s) : memory

## names : ind, dep

## min values : 21, 20

## max values : 75, 71

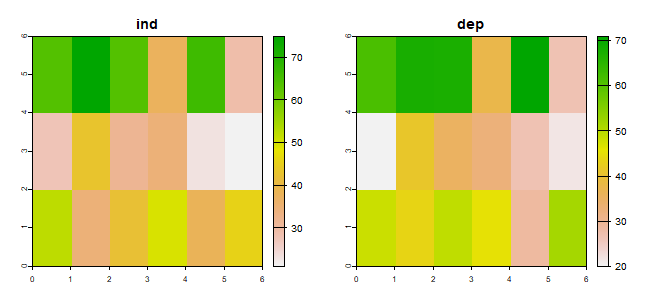

plot(s1)

Below I coerce the SpatRaster into a data.frame. In R, most

functions for statistical analysis want the input data as a

data.frame.

d1 <- as.data.frame(s1)

head(d1)

## ind dep

## 1 63.5 61.0

## 2 75.0 67.5

## 3 63.5 67.0

## 4 37.5 37.5

## 5 66.0 71.0

## 6 29.0 26.5

To recap: each matrix was used to create a SpatRaster that we

aggregated and then combined. Each of the aggregated SpatRaster

layers became a single variable (column) in the data.frame. If would

perhaps have been more efficient to first make a SpatRaster and then

aggregate.

Question 3: There are other ways to do the above (converting two

SpatRaster objects to a data.frame). Show how to obtain the

same result (d1) using as.vector and cbind.

Let’s fit a regression model again, now with these aggregated data:

ma1 <- glm(dep~ind, data=d1)

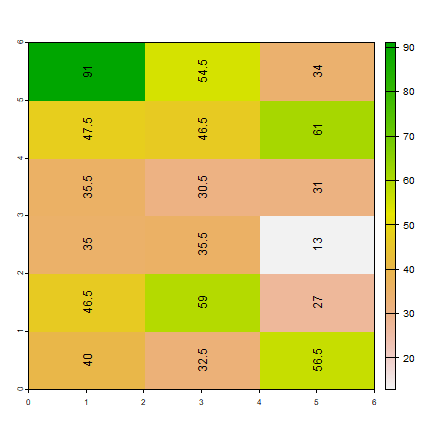

Same idea for for the other aggregation (‘Aggregation scheme 2’). But

note that the arguments to the aggregate function are, of course,

different.

ai2 <- aggregate(ri, c(1, 2), fun=mean)

ad2 <- aggregate(rd, c(1, 2), fun=mean)

plot(ai2)

text(ai2, digits=1, srt=90, halo=TRUE)

s2 <- c(ai2, ad2)

names(s2) <- c('ind', 'dep')

# coerce to data.frame

d2 <- as.data.frame(s2)

ma2 <- glm(dep ~ ind, data=d2)

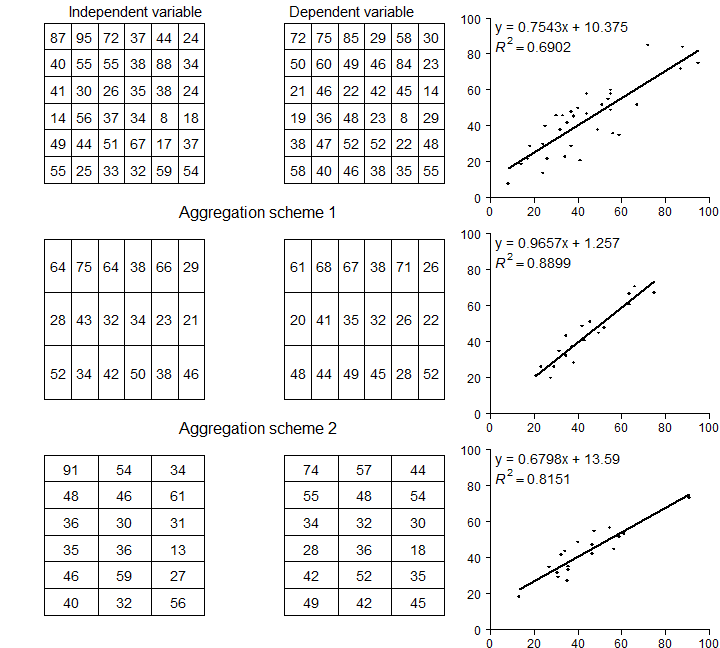

Now we have three regression model objects. We first created object

m, and then the two models with aggregated data: ma1 and

ma2. Compare the regression model coefficients.

m$coefficients

## (Intercept) ind

## 10.3749675 0.7543472

ma1$coefficients

## (Intercept) ind

## 1.2570386 0.9657093

ma2$coefficients

## (Intercept) ind

## 13.5899183 0.6798216

Re-creating figure 2.1 takes some effort. We want to make a similar

figure three times (two matrices and a plot). That makes it efficient

and practical to use a function. Look

here if you do not

remember how to write and use your own function in R:

The function I wrote, called plotMAUP, is a bit complex, so I do not

show it here. But you can find it in the source

code for this page. Have a look at

it if you can, don’t worry about the details, but see if you can

understand the main reason for each step. It helps to try the lines of

the function one by one (outside of the function).

To use the plotMAUP function, I first set up a plotting canvas of 3

rows and 3 columns, using the mfrow argument in the par

function. The par function is very important for customizing plots —

and it has an overwhelming number of options to consider. See ?par.

The mai argument is used to change the margins around each plot.

# plotting parameters

par(mfrow=c(3,3), mai=c(0.25,0.15,0.25,0.15))

# Now call plotMAUP 3 times

plotMAUP(ri, rd, title=c('Independent variable', 'Dependent variable'))

# aggregation scheme 1

plotMAUP(ai1, ad1, title='Aggregation scheme 1')

# aggregation scheme 2

plotMAUP(ai2, ad2, title='Aggregation scheme 2')

Figure 2.1 An illustration of MAUP

Distance, adjacency, interaction, neighborhood

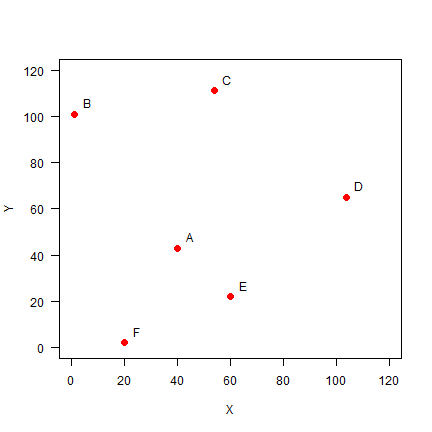

Here we explore the data in Figure 2.2 (page 46). The values used are not exactly the same (as they were not provided in the text), but it is all very similar.

Set up the data, using x-y coordinates for each point:

A <- c(40, 43)

B <- c(1, 101)

C <- c(54, 111)

D <- c(104, 65)

E <- c(60, 22)

F <- c(20, 2)

pts <- rbind(A,B,C,D,E,F)

head(pts)

## [,1] [,2]

## A 40 43

## B 1 101

## C 54 111

## D 104 65

## E 60 22

## F 20 2

Plot the points and labels:

plot(pts, xlim=c(0,120), ylim=c(0,120), pch=20, cex=2, col='red', xlab='X', ylab='Y', las=1)

text(pts+5, LETTERS[1:6])

Distance

It is easy to make a distance matrix (see page 47)

dis <- dist(pts)

dis

## A B C D E

## B 69.89278

## C 69.42622 53.93515

## D 67.67570 109.11004 67.94115

## E 29.00000 98.60020 89.20202 61.52235

## F 45.61798 100.80675 114.17968 105.00000 44.72136

D <- as.matrix(dis)

round(D)

## A B C D E F

## A 0 70 69 68 29 46

## B 70 0 54 109 99 101

## C 69 54 0 68 89 114

## D 68 109 68 0 62 105

## E 29 99 89 62 0 45

## F 46 101 114 105 45 0

Distance matrices are used in all kinds of non-geographical applications. For example, they are often used to create cluster diagrams (dendograms).

Question 4: Show R code to make a cluster dendogram summarizing the

distances between these six sites, and plot it. See ?hclust.

Adjacency

Distance based adjacency

To get the adjacency matrix, here defined as points within a distance of

50 from each other is trivial given that we have the distances D.

a <- D < 50

a

## A B C D E F

## A TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE

## B FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

## C FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE

## D FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE

## E TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE

## F TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE

To make this match matrix 2.6 on page 48, set the diagonal values to

NA (we do not consider a point to be adjacent to itself). Also

change the change the TRUE/FALSE values to to 1/0 using a simple

trick (multiplication with 1)

diag(a) <- NA

adj50 <- a * 1

adj50

## A B C D E F

## A NA 0 0 0 1 1

## B 0 NA 0 0 0 0

## C 0 0 NA 0 0 0

## D 0 0 0 NA 0 0

## E 1 0 0 0 NA 1

## F 1 0 0 0 1 NA

Three nearest neighbors

Computing the “three nearest neighbors” adjacency-matrix requires a bit

more advanced understanding of R.

For each row, we first get the column numbers in order of the values in that row (that is, the numbers indicate how the values are ordered).

cols <- apply(D, 1, order)

# we need to transpose the result

cols <- t(cols)

And then get columns 2 to 4 (why not column 1?)

cols <- cols[, 2:4]

cols

## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## A 5 6 4

## B 3 1 5

## C 2 4 1

## D 5 1 3

## E 1 6 4

## F 5 1 2

As we now have the column numbers, we can make the row-column pairs that

we want (rowcols).

rowcols <- cbind(rep(1:6, each=3), as.vector(t(cols)))

head(rowcols)

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 5

## [2,] 1 6

## [3,] 1 4

## [4,] 2 3

## [5,] 2 1

## [6,] 2 5

We use these pairs as indices to change the values in matrix Ak3.

Ak3 <- adj50 * 0

Ak3[rowcols] <- 1

Ak3

## A B C D E F

## A NA 0 0 1 1 1

## B 1 NA 1 0 1 0

## C 1 1 NA 1 0 0

## D 1 0 1 NA 1 0

## E 1 0 0 1 NA 1

## F 1 1 0 0 1 NA

Weights matrix

Getting the weights matrix is simple.

W <- 1 / D

round(W, 4)

## A B C D E F

## A Inf 0.0143 0.0144 0.0148 0.0345 0.0219

## B 0.0143 Inf 0.0185 0.0092 0.0101 0.0099

## C 0.0144 0.0185 Inf 0.0147 0.0112 0.0088

## D 0.0148 0.0092 0.0147 Inf 0.0163 0.0095

## E 0.0345 0.0101 0.0112 0.0163 Inf 0.0224

## F 0.0219 0.0099 0.0088 0.0095 0.0224 Inf

Row-normalization is not that difficult either. First get rid if the

Inf values by changing them to NA. (Where did the Inf values

come from?)

W[!is.finite(W)] <- NA

Then compute the row sums.

rtot <- rowSums(W, na.rm=TRUE)

# this is equivalent to

# rtot <- apply(W, 1, sum, na.rm=TRUE)

rtot

## A B C D E F

## 0.09989170 0.06207541 0.06763182 0.06443810 0.09445017 0.07248377

Divide the rows by their totals and check if they row sums add up to 1.

W <- W / rtot

rowSums(W, na.rm=TRUE)

## A B C D E F

## 1 1 1 1 1 1

The values in the columns do not add up to 1.

colSums(W, na.rm=TRUE)

## A B C D E F

## 1.3402904 0.8038417 0.9108116 0.8166821 1.2350790 0.8932953

Question 5: Show how you can do ‘column-normalization’ (Just an exercise, in spatial data analysis this is not a typical thing to do).

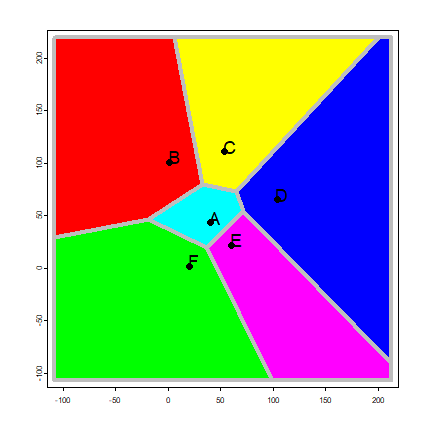

Proximity polygons

Proximity polygons are discussed on pages 50-52. Here I show how you can

compute these with the voronoi function. We use the data from the

previous example.

vp <- vect(pts)

v <- voronoi(vp)

Here is a plot of our proximity polygons (also known as a Voronoi diagram).

par(mai=rep(0,4))

plot(v, lwd=4, border='gray', col=rainbow(6))

points(vp, pch=20, cex=2)

text(vp, toupper(letters[1:6]), pos=4, cex=1.5, halo=TRUE)

Note that the voronoi functions returns a SpatVector. This is a

class (type of object) that can be used to represent geospatial polygons

in R.

class(v)

## [1] "SpatVector"

## attr(,"package")

## [1] "terra"

v

## class : SpatVector

## geometry : polygons

## dimensions : 6, 0 (geometries, attributes)

## extent : -108, 213, -107, 220 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

## coord. ref. :